Feedback on the National Health Insurance Bill

Published on: 14 October 2019

Introduction

The South African Academy of Family Physicians is the professional body for family medicine in South Africa. Our membership (of over 600) includes mostly family physicians, but also registrars in training to become family physicians, as well as some general practitioners, medical officers and other primary care providers.

Dr Phaahla, the Deputy Minister of Health, addressed our national conference in August and invited us to give constructive feedback on the NHI Bill. The theme of the conference was “The primary health care team: roles and alignment to the ideals of NHI”.

We asked our member to provide feedback on the NHI Bill and to respond to three key questions:

Q1. Do you have any concerns regarding the implementation of NHI as outlined in the Bill?

Q2. Do you have any questions of clarification about NHI as described in the Bill?

Q3. Do you have any suggestions on how NHI could be implemented better?

Their answers to these questions were analysed with the help of Atlas-ti and are summarised below.

Respondents

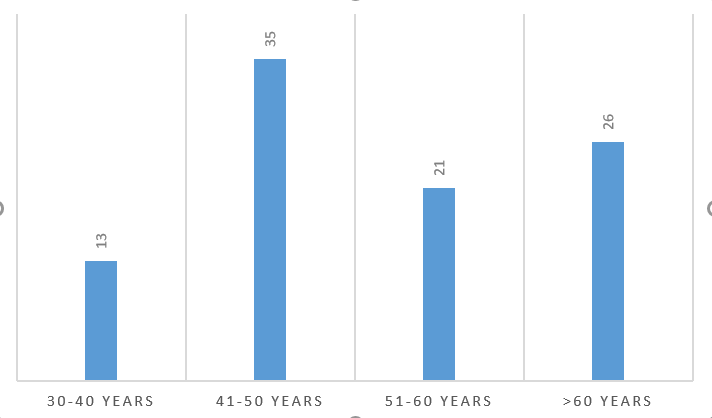

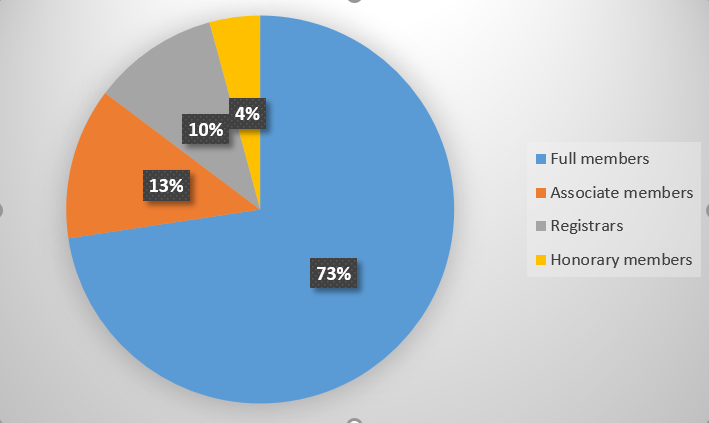

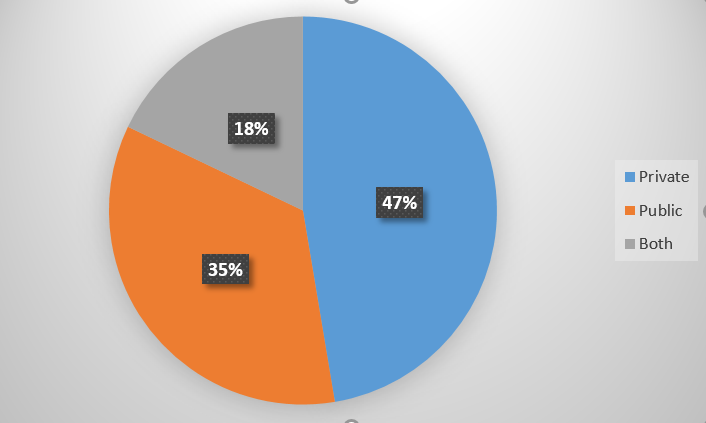

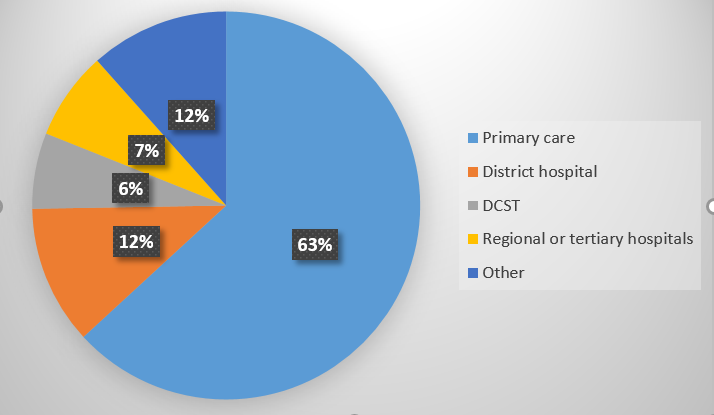

We had 95 members that responded to the questions. The majority were middle aged, male (77%), family physicians (73%) in private practice (65%) and working in primary care (63%). See Figures 1-4.

Concerns regarding the implementation of NHI

Almost all respondents had concerns regarding the implementation of NHI.

Poor quality public sector health services

The current public sector health system was seen as ailing (shortages of health professionals, poor infrastructure, financial constraints, inadequate equipment) and struggling to provide an acceptable standard of care, both in terms of fulfilling the requirements for NHI accreditation, as well as the expectations of an expanded pool of users under NHI, who would previously have had medical aid.

Managerial capability

Members were concerned at a lack of leadership and managerial capability in the public sector that would impede the implementation of NHI. Managers might be appointed for their political connections, rather than competency. Respondents felt that gross mismanagement has plagued healthcare in many provinces and this might carry over to poor management of NHI.

Possibility of corruption and poor governance

A widely expressed concern was the possibility of corruption, given the history of state-capture and corruption in other state owned enterprises and provinces. Corruption might lead to the misappropriation of funds at different levels in the NHI system.

Members were concerned that the Minister of Health had too much personal and political control over the appointment of NHI governance structures and that there was too little oversight of this power. This leads to a future risk for a lack of accountability as well as patronage and corruption.

Insufficient funds

Members were concerned that the relatively small tax base to fund NHI would not be sufficient to pay for a comprehensive package of care for all in the South African context. Government entities such as NHI would find it difficult to borrow money and would be dependent on tax funded government bail outs should shortfalls arise. No provision is made for a pool of reserves. Limited funds might then lead to restrictions on what services were covered. Tax payers would then have to pay for NHI, but all might receive a less comprehensive package of care than what is currently available.

Financial planning

There was concern that no detailed costing of the NHI model had been published and that this represents a lack of due diligence on the part of those planning to implement the model.

Administrative capacity

Members were concerned that inefficient public sector administration and bureaucracy would impede the implementation of NHI.

The concept of “timely” remuneration is not defined in the Bill, which leaves the payment of providers open ended. There should be a legal requirement to pay within 30 days.

Timeframe

Several respondents felt that the time frame was unrealistic and implementation too fast given the many issues that need to be solved to make it a success.

Effect on health professionals

Uncertainty and fears that remuneration may decrease and workload increase in the private sector may prompt some doctors to emigrate. Fears that NHI will lead to increased workload and reduced quality of life for practitioners.

There is uncertainty about the place for other members of the multidisciplinary team in the services funded by NHI –e.g. mid-level workers, pharmacists, therapists.

The possibility to earn extra income in the private sector may be reduced.

Outcomes for patients

Several respondents saw NHI as benefiting people from lower socio-economic groups, while a few believed that they might even be worse off.

There was a concern that many patients would experience a decline in their quality of care with longer waiting times and waiting lists.

There was some comment that NHI erodes ones autonomy to freely choose one’s own service providers and one’s rights as a consumer.

Employed people currently on medical insurance may be expected to pay for NHI, receive a lower standard of care and in addition pay for additional medical insurance for what is not covered by NHI.

Legal framework and definitions in the Bill

Many aspects of the NHI Bill contradict existing legislation and this may take time to address properly.

The role of provinces seems to be minimised in the Bill and changes in their role may lead to legal or constitutional challenges.

The concept of “appropriated resources” in the Bill needs to be explained or defined and is a worrying possibility.

The dominance of the NHI Bill over other legislation such as Children’s Act, POPI, Consumer Protection, Health Professions Act, may erode consumer rights and ethical medical practice.

Excluding NHI transactions from the Competition Law could lead to higher prices with less competition, allow suppliers to collude on higher prices or threaten withdrawal of services if tariffs do not suit them.

The requirements to record information in practices that opt out of NHI may conflict with the autonomy of patients to not provide this information.

Illegal foreigners will find it difficult to access health care under NHI and having different tiers of access (they will be able to access care for notifiable conditions) will be administratively complicated. There may also be a contradiction between the constitution, which speaks of the right to health care for everyone, and the NHI Bill which restricts health care for certain groups.

How will the state determine what are “reasonable” or “unreasonable” grounds to deny people health care as stated in the Bill.

The administrative requirements to fulfil 6(b) and communicate to all citizens might be beyond capacity to deliver.

It is not clear if the military who are excluded from NHI will still have to fund NHI through taxation.

It is not clear whether NHI will contract with health care service providers, who are juristic persons, or with public entities such as hospitals and clinics. Hospitals and clinics cannot contract with the NHI currently as they are not juristic persons and would have to go through a process of being registered as per the legal requirements. The employment status of the employees of these hospitals and clinics might then need to change.

The Bill implies that it may negotiate prices for health services (11.2e), while elsewhere implying that NHI will set prices for capitation and services.

The Bill says nothing about traditional practitioners.

The Bill appears to provide loopholes for medical schemes to offer the same services to patients who skip the referral chain, who consult non-contracted healthcare professionals or to foreigners who are not covered.

The Bill appears to place the responsibility on practices to transfer patients to another facility if they cannot provide the care needed – who will pay for this? This needs to be clarified.

What benchmark will be used to determine a reasonable waiting time for services and what recourse will people have if this is not met. This should be defined.

Questions of clarification

Uncertainty and fear

Responses were characterised by misunderstandings, uncertainty and fear of the future in a national context that was portrayed as economically insecure and ridden by corruption. This led to many comments about emigrating.

There is a clear need for more detail in all aspects of NHI such as funding, accreditation, remuneration, patient registration and so on. Communication needs to address the concerns of doctors in straightforward language that makes what is known and yet to be decided also clear. Ongoing and multifaceted forms of engagement and dialogue need to be created.

Accreditation of practices

Members asked questions about what standards will be used to accredit practices and how non-compliant practices will be handled. There was a belief that many public sector facilities will not be compliant. In addition questions were asked about the capacity of the OHSC to also assess all the eligible private facilities. In rural and remote areas the only services may be in the public sector and yet they may not meet the standards for accreditation, what will then happen?

It was not clear how the contracting units would actually function and what their composition would be.

Doctors wanted to know:

• how solo private GP practices would be accommodated,

• whether all primary care facilities would need to have a doctor,

• whether junior doctors (<10 years of experience) would be obligated to have a Diploma in Family Medicine for primary care

• whether family physicians would be recognised as specialists in the accreditation and remuneration process in districts.

• whether doctors in private practice would be required to relocate or change their hours of practice.

Registration of patients

Doctors had queries regarding the registration of patients with whom they already had an established relationship, will they be allowed to retain these patients? Was there a certain number of patients that would be required, particularly for solo practitioners? How would patients that are not registered with your practice be dealt with, for example foreigners or people from other provinces?

A related issue is how workload will be divided between facilities that are currently seen as public or private facilities.

The requirements for biometrics and photographs to register patients may require investment in new equipment at all facilities – is this really feasible or warranted? Who will provide this equipment?

Future of medical aids

Doctors in private practice wanted to know if they would be able to see both NHI and medical aid patients. They were not clear what would happen to medical aids under NHI and what they will be able to do or not do. Many suspected that this would be the death of medical aids and that patients would not be able to afford both NHI and medical aids.

Employment issues

Doctors in both the public and private sectors had queries regarding who would be employing them in future and how much they would be paid. There was confusion as to whether doctors in private practice would now be employed by the state. In addition there were queries regarding the implications for numbers of posts and whether the new system would enable all doctors to find employment.

Clinical practice issues

Doctors wanted to know the implications for their scope of practice. The package of care is not yet clearly defined.

Doctors were uncertain as to whether GPs would have the capacity to act as gatekeepers for all patients to the healthcare system. The way in which referral pathways would work in future was also not clear as both public and private hospitals would be included under NHI.

Private hospitals

There was uncertainty about what would happen to private hospitals, their staff and specialists under NHI. How would the equipment and infrastructure that they have invested in be incorporated under NHI?

Quality and safety

How will quality assurance and improvement be implemented under NHI and how will unsafe or negligent doctors be handled. Doctors also asked about medical liability cover for them under NHI.

Remuneration

Many doctors were unclear as to whether this would be a capitation-based system and how this would work. Some envisaged becoming salaried employees of the state others still using fee for service. The bottom line was how much would the income be and would this be sufficient to provide the service, be sustainable and take home a reasonable amount.

Doctors also wanted to know what penalties or accountability there would be if NHI did not pay them in a reasonable time period.

Medication

What will the role of government be in the procurement and dispensing of medication?

Training of students

Currently the public sector is used to train health professionals and interns, under NHI will all accredited practices be required to accept students and expose patients to them. How will NHI influence the training platform? Some felt that the training of doctors in the country had deteriorated. NHI needed to give recognition to those facilities engaging with training and research.

Suggestions regarding implementation

Communicate and engage much more proactively with health professionals

Again the need for a major campaign to win ‘hearts and minds’ to the need for and the plans for NHI was emphasised. Health professional’s fears and uncertainties need to be addressed and buy-in obtained. Doctors need clarification and detail on how accreditation, remuneration, patient registration and the package of services will work.

The public and civil society also need active engagement.

Revise the approach to governance and clarify funding model

Respondents felt strongly that governance of NHI should have more independence from politicians, maybe even a separate organisation from the DOH. A clear funding model and plan needs to be developed and presented.

Strengthen the current public health system first

This group felt that a pre-requisite for introducing NHI should be the improvement of service delivery in the public sector and that this should be demonstrated first. They felt that improvements were needed in financial resources, management competency and efficiency, leadership style (moving away from command, control, expected obedience), administrative efficiency, supply chain (medication, equipment etc.), quality and safety, human resources (both numbers and competencies, including posts for family physicians), monitoring and evaluation (feedback on performance needed).

Implement incrementally and more slowly

They felt that the so called NHI pilot districts had not really piloted NHI as in the Bill. More piloting was needed of the key elements e.g. contracting units. Go more slowly.

Some felt that more attention needed to be given to develop services in rural areas within the NHI initiative.

Do not destroy the quality of the private health care system in the process

This group were worried that NHI would pollute the private sector with the same problems as faced by the public sector and destroy the high quality of private healthcare.

Start by harnessing resources and competencies in the private sector to strengthen the public sector

They did however feel that the private sector could assist the public sector to improve through public-private partnerships whereby, for example, private clinics and hospitals saw more patients funded by state or NHI. They also felt that administrative systems and expertise in the private sector (e.g. IPAs with managed care capitation schemes) could assist with developing systems for NHI.

Some felt that medical aids should be allowed to continue insuring the same services as offered under NHI. Some felt that doctors should continue to be allowed to do both public and private care.

One suggested that government subsidy of private health care could also be reduced and redirected to the public sector.

Do not implement NHI

There was a small group that felt that it would be unaffordable, unmanageable and ineffective. They also felt that while keeping the status quo more effort should be made to improve the quality of public sector healthcare.

![Family Physicians logo[transparent]](https://saafp.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Family-Physicians-logotransparent-1200x266.png)